Lesser Sandhill Crane

(Antigone canadensis canadensis)

Sandhill Crane (Photo by Nina Faust)

General Information

There are 15 crane species in the world. Two of those species – the Sandhill Crane and Whooping Crane – breed in the United States. There are six subspecies of the Sandhill Crane: Greater, Lesser, Canadian, Mississippi, Florida, and Cuba. Our Homer Cranes are of the Lesser Sandhill Crane subspecies.

The Sandhill Crane is a member of the Gruidae family; and was formerly in the genus Grus, but was recently reclassified to the Antigone genus. The species remains the canadensis.

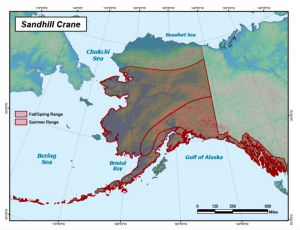

Range: There are two flyways for the Lesser Sandhill Crane: Central and Pacific.

The Central Flyway population spends summers in Canada, northern Alaska, and the Siberian Peninsula; overwintering in Mexico, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico.

The summer breeding grounds for the Pacific Flyway population is Southcentral Alaska (including Homer) and along the Alaska Peninsula. This population overwinters in the Central Valley of California – Sacramento area.

Source: International Crane Foundation.

Alaska Range Map

Source: Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: Cranes are large, wading birds with long necks and legs, and a characteristic feathered tail bonnet, red crown, and long menacing beak. Their legs are black, and their plumage varies from shades of grey, brown, and rust. Juveniles have cinnamon-brown feathers and lack the red crown.

Lesser Sandhill Cranes typically weigh around 7.5 lbs and reach a shoulder height of 34-48 inches. Males and females are generally indistinguishable; here’s a tip: when giving an alert call or territorial call the males bring their head back 90 degrees (beak straight up in the air), while the female brings her head back only about 45 degrees (See photo below).

Lesser Sandhill Cranes have an impressive wingspan of 6-8 feet. When spotted flying overhead, look for slow rolling downbeats, and quick upbeats of those large wings. You can generally tell when cranes are ready to fly as they may show agitation, ‘crane’ their neck, and then take a few steps prior to taking off.

In the wild, a crane that survives the first year, generally has a life span of around 20-30 years. Cranes do not begin breeding until around four years of age.

Cranes use an iron oxide mud to paint their feathers. Painting, is believed to help camouflage the cranes from predators especially while the crane is on the nest. The crane will take a bundle of grass and dip it in the mud and then apply the mud to its feathers.

Preferred Habitat: Cranes inhabit a variety of open wetland and upland habitats for nesting and loafing. For roosting, cranes seek out wet areas or islands, which are safer from predators.

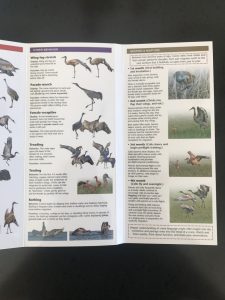

Crane Display: Cranes have a variety of display postures to signal different activities, including:

- When to fly

- Attack and threat

- Receptivity to breeding

And, how we enjoy watching cranes dance, especially during courtships as they jump and hop while spreading their wings, with an animated bowing to another crane – often like mirror images.

Want to learn more about Sandhill Crane displays? Check out the Sandhill Crane Display Dictionary: What Cranes Say with Their Body Language, by Yunker Happ. Go to: www.AlaskaSandhillCrane.com This field pamphlet is available at the Homer Bookstore, the Islands and Ocean Visitor Center, or Center for Alaskan Coastal Studies.

Reproduction: Cranes form pair bonds and mate for life (divorce does happen and a crane that loses a mate will bond again). Breeding begins around four years of age. They have low reproductive rates, in part, due to being long-lived birds.

Breeding Season: In the Homer area, the breeding season begins soon after the long-anticipated arrival of the cranes in late April/early May.

Nesting: The nest is nothing fancy, the main criteria is camouflage. Cranes are ground nesters, building simple nests of dry grasses and feathers, in the shape of a shallow depression.

The preferred nest site is an area protected from predators, with a preference for wetlands and islands. However, cranes in the Homer area haven’t read the memo and are found nesting in upland areas as well. A three-year crane nesting survey of the Homer Area, from 2011-2013, found 30 known nesting pairs and the probability that more remote nests were never reported or found.

A master of camouflage – look carefully above the piece of wood on the lower right side of the photo.

Eggs and Incubation: The female generally lays two eggs, and if a crane pair experiences nest disturbance/abandonment early in the incubation period, they may nest again and lay additional eggs. Chicks hatch within 30 days.

Both parents incubate the eggs, however, the male’s primary task is to maintain the integrity of the territory. Incubating pairs trade places about every two hours during daylight hours. This gives each bird a chance to stretch, exercise, and feed. At night, the female incubates while the male stands guard. The male is often the first to feed the chicks.

The photos below show various crane nests; one with an egg; one with egg shell fragments (all photos by Michelle Michaud).

Nesting success is often dependent on habitat selection. Egg loss can be due to abandonment, or predation (eagles, ravens, crows, gulls, dogs, coyotes, and lynx), or being stepped on by moose.

Prior to fledging, the colt is flightless and very susceptible to predation. Colt loss can be due to a number of factors: predation, especially by eagles and dogs, lack of food, or parental neglect; or exceptionally bad weather, like wind and rain or snow in early spring. Photos by Nina Faust.

Fledging: Colts fledge within 60-70 days. They stay with their parents for 9-10 months. When the parents return to the breeding grounds, the adults chase off the colts to start a new family. These colts have now gained the red coloring on their heads, as well as the yellow eyes of an adult, and will join a group of non-breeding subadults — the crane equivalent of a roaming band of juveniles.

Not all crane colts survive to fledging. In Homer in 2017, 29 known breeding pairs produced 54 colts, of which only 34 colts fledged.

Food Preferences: Cranes are omnivores – eating frogs, voles, shrews, insects, bulbs, seeds, berries, and even baby ducklings.

Homer cranes are habituated to humans, especially when fed whole or cracked corn. Such feeding, however, is not necessary. There is sufficient food available in the wild for the cranes to obtain the nutrients needed for growth and survival. Feeding Cranes in an urban setting can be detrimental to the crane as it exposes them to predators, especially dogs and eagles. The urban habitat often lacks good nesting sites and natural sources of protein necessary for chick development. Other urban hazards affecting crane mortality include collisions with electrical power lines and vehicles, attacks by roaming neighborhood dogs, and poisoning from pesticides used on lawns. Also cranes can become aggressive protecting their young and can injure pets or humans.

Roosting: Cranes roost in large flocks, generally in shallow bodies of water to avoid predation. Cranes with colts that have yet to fledge roost separately, generally near the nest site (within their breeding territory).

Population Estimate: According to Kachemak Crane Watch, the Sandhill Crane population in the Homer Area (Anchor Point south to Kachemak Bay) is stable at around 200-250 individuals recorded annually.

Migration: In 2008, a study sponsored by Kachemak Crane Watch and conducted by the International Crane Foundation, sought to discover the migration route and wintering grounds of Homer area Sandhill Cranes. Ten (10) cranes were captured and fitted with satellite and radio transmitters. The study revealed several key findings: migration route, where the cranes winter (Central Valley of California), amount of time needed to reach their breeding and wintering grounds, and where they stopped during migration to refuel (See Figure 1 below). The journey from Homer to the Central Valley of California is approximately 2,400 miles – one way! The cranes take approximately one month during the fall migration to reach the Central Valley of California and approximately two months during spring migration return to Homer. They may spend up to a week or more at a staging area along the route in order to “refuel” for the long journey.

Figure 1: Map showing the transmitter data of the migration route of the Homer area banded cranes, including the different staging areas where they spent some stop-over time en-route to their breeding and wintering grounds. You can find this figure at: http://cranewatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/annual_travels_sh_cranes_homer_map.pdf

Vocalizations: Sandhill Cranes have several calls, but the most distinctive is the unison call – a loud, resonant bugle.

Listen now to the unison call

Threats: Habitat loss is a primary threat – loss of wetlands, grasslands and agricultural fields being developed, conflicts with agriculture, afforestation (trees taking over grasslands), conflicts with living in urban areas. Other threats include; drought, predation, impacts with vehicles, pesticide use on lawns and gardens, and collisions with power lines.

Hunting: Sandhill Cranes are hunted in Alaska for sport and subsistence, although they are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA). Hunting season begins in September, prior to migration. A number of other states also allow hunting of Sandhill Cranes, including Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Fun Facts:

- Sandhill Crane chicks are called “colts”.

- Three pairs of Sandhill Cranes breed in Beluga Slough. One pair breeds near the boardwalk trail by the Islands and Ocean Visitor Center. You can watch this pair raise their colt(s) during the summer months.

- Kachemak Crane Watch co-founder Nina Faust is an accomplished videographer of Homer Sandhill Cranes. Nina produced a wonderful video called “Raising Kid Colt: A Story of a Young Sandhill Crane.” You will experience, up close, the intimate world of a Sandhill Crane’s family life, which includes seldom-seen perspectives of raising crane colts, as well as a progression of colt development over the summer. You can check out all her crane videos by going to the Kachemak Crane Watch website: cranewatch.org.

- Prior to fall migration, cranes will begin gathering in large groups. When the September weather conditions present a high pressure bringing upper air currents from the northwest, the cranes will circle the sky – called ‘kettling’ and the gathering group will then head towards their wintering grounds – a spectacle to see.

- Our Homer Cranes typically migrate south by the middle of September. You can enjoy the nightly “fly-in” of cranes at Beluga Slough as they begin to gather prior to migration.

- The Tanana Valley Sandhill Crane Festival (Fairbanks) is held every year in late August. This three-day event features field trips, workshops, and a great opportunity to see and learn more about Sandhill Cranes.

- A crane fossil was found in Nebraska dating from the Pliocene period (5.3-2.6 million years ago). The fossil appears structurally identical to the modern Sandhill Crane. That would make the Sandhill Crane one of the oldest known bird species!

Conservation Status: The Sandhill Crane is a species of Least Concern, with populations generally increasing. Of concern is habitat loss and drought in California’s Central Valley, which significantly affects the Pacific Flyway population of Sandhill Cranes. The Pacific Flyway population is much smaller (approximately 20,000 birds) than the Central Flyway population (approximately 450,000 birds). The Central Flyway population are those cranes that make their way north through the Platte River in Nebraska.

In Homer, Kachemak Crane Watch (KCW) is dedicated to the protection of Sandhill Cranes and their habitat in the Kachemak Bay area.

The 2018 breeding season is fast approaching. Become a “Citizen Scientist”- KCW has been monitoring the Homer area crane population for over 15 years with the help of citizen scientists. With your help, KCW seeks information on:

- distribution and abundance of cranes from Anchor Point to the head of Kachemak Bay;

- nests and colts (chicks);

- population numbers;

- arrival and departure dates; and

- mortality due to eagle predation, dogs, and other causes.

Report your observations to Kachemak Crane Watch at 907-235-6262 or email report@ cranewatch.org.

Crane Species in Alaska: Only the Lesser Sandhill Crane subspecies is found in Alaska.

More Information:

For more information about Homer area Sandhill Cranes go to: www.cranewatch.org

For more information about all subspecies of Sandhill Cranes go to International Crane Foundation at: https://www.savingcranes.org/species-field-guide/sandhill-crane/.

Sources of Information:

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Species Profile: Sandhill Crane. http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=sandhillcrane.main

All About Birds. 2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Sandhill_Crane/

Bailey, E. and Faust, N. 2017. Lesser Sandhill Cranes, Annual Summary. Homer, Alaska, Summer 2017. http://cranewatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Annual-Summary-2017.pdf

International Crane Foundation. Sandhill Crane. 2018. https://www.savingcranes.org/species-field-guide/sandhill-crane/

International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-3. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 15 March 2018.

Sibley, David Allen. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Andrew Stewart Publishing, Inc.

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

Yunker Happ, C. 2015. Sandhill Crane Display Dictionary: What Cranes Say with Their Body Language. Waterford Press.