Wilson’s Snipe

(Gallinago delicate)

General Information: The Wilson’s Snipe, a member of the Cholopacidae family, genus Gallinago, a common and widespread shorebird species, is not typically found along shorelines, but rather wetlands. The Wilson’s Snipe has a global breeding population estimated at 2 million birds.

These birds are generally not seen, since they camouflage so well, until flushed when they explode into zigzag flight, uttering their flight call.

Wilson’s Snipe is named for the ornithologist and author Alexander Wilson, who was born in Scotland in 1766, and later emigrated to America. There are four other birds named for him: Wilson’s Warbler, Wilson’s Phalarope, Wilson’s Plover, and Wilson’s Storm-Petrel.

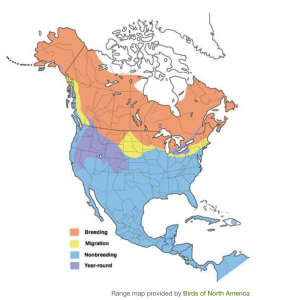

Range: The Wilson’s Snipe can be found throughout North America, breeding in several northern Lower 48 states, and in Canada and Alaska. The bird is a year-round resident of several western states, and parts of Alaska, including Kodiak Island.

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Wilsons_Snipe/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: This secretive, stocky shorebird is dark brownish overall, with bold cream-colored stripes on its neck and head. The stockiness is due to extra-large pectoral muscles. Snipe weigh in at 3.7 ounces (yes, about 1/3 of a pound), and are 10-11 inches in length.

Snipes may form loose groups of up to 10, but are generally a solitary bird.

Preferred Habitat: Although a “shorebird”, these birds prefers moist habitat, such as wetlands (marshes, bogs, and willow/alder swamps) during the breeding season. During migration and on the wintering grounds they prefer damp areas with vegetative cover, such as wet fields, marshes, and ditches.

Breeding Season: Breeding begins in mid-May, which is a great time to hear and, with luck, see a male Wilson’s Snipe performing his aerial display where they zigzag across the sky at speeds of up to 60 miles per hour. Listen for the distinctive winnowing display sound as you try to locate the bird high above.

Nesting: Wilson’s Snipe are ground nesters. The female builds the nest – a shallow scrape in moist soil. She weaves a lining of coarse grasses, building a nest up to 3 inches deep, and 7 inches across. Once that is accomplished, she then adds finer grasses inside; and takes a few more grasses or sedges (sedges have edges) from the edge of the nest for placement in the nest.

Eggs and Incubation: The female has full incubation responsibility, laying four eggs, which she incubated for 18-20 days. Hatching is asynchronistic, meaning eggs hatch at different times. Only one brood per season is common, and then re-nesting may occur.

Fledging: The young snipes are able to fly within 19-20 days of hatching. Once the chicks fledge, the parents separate with the male taking and caring for the two oldest chicks, and the female the two youngest chicks.

Food Preferences: The Wilson’s Snipe by probing for aquatic invertebrates – primarily insect larvae, but also crustaceans, earthworms, and mollusks.

Feeding Methodology: Wilson’s Snipe stick their long beaks deep into the soil or shallow water as they probe for their food – sewing machine style. They may occasionally use foot stomping or bouncing to locate – ‘scare up’ – prey. Snipe are active feeders day and night, so your chances are good to see one if you look closely (they camouflage well). The bill has a flexible tip allowing the bird to open it to grasp food while the base of the bill remains closed. This allows them to ‘slurp up’ prey without removing their bills from the soil.

Roosting: They are often spotted standing on fence posts and in trees or dense vegetation.

Migration: Wilson’s Snipe generally arrive in the Homer area in late April or early May. They are readily identified by their spiraling flight display and the winnowing sounds that result from air moving through their tail feathers.

For those birds that migrate, spring migration is from late February through late May. Fall migration is from mid-July to December. The snipe migrate mostly at night.

In some parts of the U.S., Wilson’s Snipe are year-round residents – aren’t those birders lucky. The bird winters in the United States, Central America, and as far south as Venezuela.

Vocalizations: Flight call is a harsh “scrape”. The perch display song is a loud, repeating “TIKa” or “TUKa” sound. And of course, the “hu-hu-hu-hu-hu” winnowing sound is made during flight display, when the air moves through the bird’s tail feathers.

The Cornell Lab of Ornthology has gracious provided us with the call and flight display sounds of the Wilson’s Snipe.

Call

Flight Display

Threats: Most states do allow hunting of snipe. Hunters consider them a challenge with their explosive, surprising, flushing from their concealment. Between 2006 and 2010, approximately 105,000 snipe were taken annually by U.S. and Canadian hunters. This number is believed to be considerably lower than the number of snipe hunted for “sport” during the mid-twentieth century.

Other threats include loss of wetland habitat due to conversion and draining; and collisions with radio, TV, and cell towers, powerlines, buildings (glass), and vehicles.

Fun Facts:

- Have you noticed how far back on the head the snipe’s eyes are set? This allows the bird to see a potential predator sneaking up on a feeding snipe. This bird almost literally has “eyes on the back of its head”.

- Snipe can reach flight speeds up to an estimated 60 miles per hour due to massive flight muscles, which gives the snipe its “stocky” look.

- “Going Snipe hunting” is often considered a childhood prank.

- Did you know the word “sniper” originated among British soldiers in India during the 1770s as they hunted for snipe? While snipes are still hunted worldwide, their fast, erratic flight style makes them difficult targets.

- Research on the winnowing sound generated by the snipe’s outermost tail feathers (retrices) reveals that it occurs at air speeds of approximately 25 miles per hour.

Conservation Status: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) have identified the Wilson’s Snipe as a species of Least Concern on their Red List of Threatened Species. However, they also note that the population trend for the species is decreasing. Wilson’s Snipe do not appear on the Alaska Audubon’s Watchlist.

Snipe Species in Alaska: Occasionally the Common Snipe or Jack Snipe have been found in Alaska. Such sightings are rare.

Sources of Information:

American Bird Conservancy. Bird of the Week. https://abcbirds.salsalabs.org/birdoftheweekwilsonssnipe/index.html?wvpId=2c437645-6800-11e7-a58d-1254aa67e287. Downloaded on 15 April 2018.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology – All About Birds. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Wilsons_Snipe/id. Downloaded on 15 March 2018.

International Union for Conservation Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-3. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 15 March 2018.

North American Bird Conservation Initiative. 2016. The State of North America’s Birds 2016. Species Assessment Summary and Watch List. http://www.stateofthebirds.org/2016/resources/species-assessments/

O’Brien, M., Crossley, R., and Karlson, K. 2006. The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Sibley, David Allen. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Andrew Stewart Publishing Inc.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.

Wil Hershberger//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

William W. H. Gunn//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

IT’S A GREAT DAY TO BIRD