Arctic Tern

(Sterna paradisaea)

Photo by Michael Boylan

General Information: This species is also known as the “Mirror-winged Tern” because of its silver gray upperwings, much like a mirror. It is a common arctic and subarctic breeder, and uncommon pelagic migrant. A member of the Laridae family, its estimated population is well over 2.0 million birds. Only 10% of the population is believed to breed in Alaska. The Arctic Tern goes ‘south’ for the winter – if going to Antarctica is considered ‘going south.’

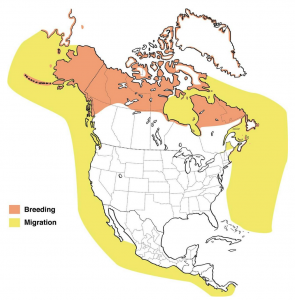

Range: Due to its long distance migration, this bird’s range is quite large. In the spring it migrates from Antarctica to the arctic and subarctic where it breeds. Come fall, it returns to Antarctic either via a western route or an eastern route. Most birds migrate via the eastern route.

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Arctic_Tern/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: A medium size tern with angular wings and pointed wingtips. All plumages show pale silvery gray and white primaries (flight feathers) with small dark tips. In breeding, the adult tern sports a black cap, long deeply forked tail, short red bill, and quite short red legs. In non-breeding plumage the legs and bill are black and the forehead white.

Preferred Habitat: Open ocean, open tundra, open boreal forests, lakes, ponds, marshes, and small rocky islands. During the winter the terns prefer Antarctic pack ice.

Breeding Season: The Arctic Tern is a circumpolar breeder, with breeding beginning in May and June. Breeding pairs form a monogamous bond during a given breeding season. They do not breed until they are 3-4 years old.

Nesting: The Arctic Tern nest in colonies in a variety of habitats: on small, rocky islands – near- shore or off-shore, open tundra, in open boreal forests, and on barrier beaches on the northeastern Atlantic coast.

Both the male and female build the nest – a shallow hollow often unlined or sparsely lined with debris and plant material, which is added while sitting on the nest – obtained within reach of the nest. Parents vigorously defend the nest, diving at and striking intruders.

Arctic terns breed on Tern Lake (appropriate name) at the junction of the Seward and Sterling Highways. Nesting terns can also be found at Potter Marsh outside of Anchorage. Terns previously nested at the Old Tern Colony on the south-side of the Homer Airport, but disturbance has caused nest abandonment.

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Eggs and Incubation: Arctic Terns lay between 1-3 eggs, which are incubated by both parents for 21-23 days. Once hatched, the young are tended by both parents. Chicks are semi-precocial (eyes open) and downy.

The young may leave the nest shortly after hatching, but they don’t travel far – staying close to the nest. Tern chicks can swim at 2 days.

Fledging: The young take wing (fly) 21-28 days after hatching, but are fed by their parents for much longer (1-2 months). These birds will not breed the following year, nor do they make the long migration north. Some may “summer” off the coast of western South America, around Peru.

Food Preferences: Arctic Terns feed on small fish, generally less than 6-inches in length (e.g., sandlances, sandeels, herring, cod, and smelt). They may also grab insects from the air or water surface, and are known to eat crustaceans, mollusks, marine worms, earthworms, and on rare occasions berries.

While in Antarctica the terns feed on krill.

Feeding Methodology: Often feeds with other terns and gulls on the open ocean, but inland generally feeds along tundra lakes, rivers, and marshes. The Arctic Tern feeds by plucking food from the water’s surface or by flying upwind, hovering briefly, then diving to catch prey below the water’s surface. I’m sure we’ve all seen this behavior.

The Arctic Tern may also forages over streams, ponds, lakes, marshes, and coastal waters. They are very aggressive toward intruders and may steal food from other birds by swooping at them causing the bird to drops its catch.

Roosting: Commonly perches on rocks, branches emerging from water, logs, and road signs. Its not uncommon to see an Arctic Tern perched on a road sign along Potter’s Marsh in Anchorage. They can often be found resting on the water.

Photo by Carla Stanley

Migration: Arctic Terns are long-distant migrants, traveling an estimated 31,000 miles during migration. How far and where a migrant travels depends upon what part of North America the bird spends the breeding season. Birds in Western North America (our Alaska birds) migrate south across the Pacific Ocean to Antarctica. Eastern North American birds migrate across the North Atlantic towards Europe and Northern Africa before heading south to Australia, New Zealand, and Antarctica. During migration they remain out to sea.

Spring migration is from March to early June. Fall migration is from July to November, peaking August to mid-September.

Vocalizations: Foraging or when taking off from the colony, Arctic Terns give a high-pitched “kip” call. Alarm call: A shrill or grating scream high in pitch.

Threats: Climate change, oil spills, environmental contaminants, predation (rats, cats, dogs, pigs, horses, cattle, etc.), human disturbance at colonies, habitat degradation, and reductions in fish stocks.

Fun Facts:

- Want to see breeding Arctic Terns then check out Tern Lake at the junction of the Sterling and Seward Highways, with a bonus of possibly seeing an American Dipper at the salmon viewing platform/bridge!

- Longest migrant – traveling upwards of 31,000 miles per year

- Some live up to 25 years, which equals more than 600,000 miles of flying in a lifetime (just think of the frequent flyer miles it earns).

- They molt their wing feathers during our winter, spending much of that time resting on small ice blocks on the edge of the Antarctic pack ice.

Conservation Status: Alaska Audubon includes the Arctic Tern on its list of Common Species Suspecting to be Declining. The tern is declining on the Arctic Coastal Plain, but has been increasing on the Yukon Kuskowkim Delta.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the Arctic Tern as a species of least concern, but noting that the species’ population is declining.

Similar Tern Species in Alaska: Aleutian Terns are found in Alaska, and occasionally in Kachemak Bay.

Sources of Information:

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds: Arctic Tern. Downloaded on April 30, 2018. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Arctic_Tern/id

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

National Audubon Society. Edited by Elphick, C., Dunning, Jr. J.B., and Sibley, D.A. 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. 2001. Alfred A. Knopf Inc.

National Audubon Society: Guide to Birds of North America. http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/arctic-tern. Downloaded on 3 May 2018.

Roger Charters/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

Sibley, David Allen. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Andrew Stewart Publishing Inc.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-3. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 03 May 2018.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.

It’s A Great Day to Bird