Want to know more about three owls that reside in the Homer Area? Read Kachemak Bay Birder Michelle Michaud’s article about the Great Horned, Boreal, and Northern Saw-whet Owls (published October 18, 2018).

Want to know more about three owls that reside in the Homer Area? Read Kachemak Bay Birder Michelle Michaud’s article about the Great Horned, Boreal, and Northern Saw-whet Owls (published October 18, 2018).

Northern Saw-whet Owl

(Aegolius acadicus)

General Information: The Northern Saw-whet Owl is a small owl about the size of an American Robin. They are members of the Strigidae family.

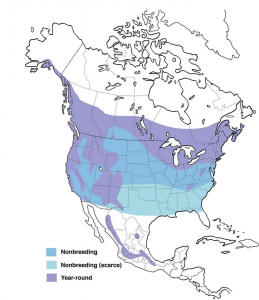

North American Range

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Saw-whet_Owl/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics/Description: Northern Saw-whet Owl is a charismatic small owl – 7.1 to 8.3 inches in height, with a wing span between 16.5 and 18.9 inches – an owl that will fit in the palm of your hand. Adults are mottled brown with a whitish facial disk and white-spotted head. Their beak is black and their eyes are yellow. Juveniles are dark brown with a cinnamon-colored breast and belly. They have large, rounded heads that lack ear tufts.

Preferred Habitat: You’ll only find these owls in the forest, preferring mature forests with an open understory (for foraging). They prefer deciduous trees for nesting and dense conifers for roosting (the better to hide), with riverside habitat nearby.

Breeding Season: Breeding season begins mid-March to mid-April, ending in late June. They are generally monogamous, however, if there is sufficient food available the male will mate with more than one female. Males begin calling (incessantly) in late January to attract a mate and to defend its territory.

Nest: The females choose the nesting location. They are secondary cavity nesters (nesting in previously excavated holes – think woodpecker hole) in dead snags. They are not known to reuse a nest cavity two years in a row.

The nest is located at the bottom of the cavity, and may consist of wood chips, twigs, moss, hair, and small mammal bones or may even be unlined. Nest cavities may be anywhere from 8-60 feet off the ground. The nest hole is generally 3inches wide and 9-18 inches deep.

Northern Saw-whet Owls also will use nest boxes (see https://nestwatch.org/learn/all-about-birdhouses/birds/northern-saw-whet-owl/ for plans on how to build a nest box). You might want to consider one for your home, provided you have the right habitat. If you install a nest box it is helpful to lay some wood chips in the bottom.

Eggs and Incubation: The female Northern Saw-whet Owl lays between 4-7 eggs (generally 5-6) with a 1 to 3-day interval between each egg, and can have up to two broods per year. The eggs are incubated by the female for 26-29 days. The young hatch in intervals, and are taken care of by the female, although the male brings food to the nest during incubation and brooding. The chicks fledge within three-weeks of hatching at which time the female and male hunt and feed the young. The young are born covered in white down, eyes closed (opening 8-9 days later). They are semi-helpless when born.

Fledging: The young leave the nest 27-35 days after hatching. However, they remain near the nest and are feed (primarily by the male) for another four weeks or more.

Food Preferences: So what do these birds like to eat? The mostly eat small mammals – mice, shrews, voles, shrew-moles, bats, and the young of chipmunks, squirrels, and gophers.

All food bets are off during migration, where they supplement their diet with birds – chickadees, juncos, sparrows, wrens, warblers, robins, waxwings, and kinglets. They may also eat insects such as grasshoppers, moths, beetles, and bugs.i

In the Homer area (coastal), they may also eat intertidal invertebrates, such as amphipods and isopods.

Feeding Methodology: These owls hunt at night (nocturnal), using both sight and sound; hunting hunt from a low perch along the forest edge flying silently and low towards prey.

Roosting: These birds roost during the daytime in dense vegetation making them difficult to see even though they are typically just above eye level.

Migration: The Northern Saw-whet Owl is both a resident and a long-distance migrant. They may migrate north/south or in altitude (moving to lower elevations in the winter). Others may remain in the same location year-round. These birds migrate at night using known migration routes across the continent. They are found year-round in Alaska, although their range is quite limited (see range map).

This owl winters in a variety of woodland habitats, but may also be found in suburban and urban areas. Spring migration begins late February and continues into May. Fall migration is from late September to December, peaking in October and early November.

Vocalizations:

Call: A rhythmic, repetitive toot, toot.

The bird is most vocal before dawn. During the breeding season the male gives this rhythmic song for hours without a break.

Threats: Habitat loss due to reduction in mature forests through logging. Climate change.

Fun Facts:

Conservation Status: The Northern Saw-whet Owl is a common species, with an estimated global breeding population around 2.0 million.

Only the Southern Appalachian Northern Saw-whet Owl population is listed on the Audubon 2014 State of the Birds Watch List. This population is at risk of becoming threatened or endangered unless conservation actions are undertaken. South Dakota and North Carolina have listed the birds as species of special concern.

The International Union of Concerned Scientists listed the Northern Saw-whet Owl as a species of least concern, with a declining population trend.

The species is not listed on Alaska Audubon’s Alaska WatchList 2017.

Similar Species in Alaska: Boreal Owl, Northern Hawk Owl

Sources of Information:

All About Birds. 2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Downloaded on 3 August 2018 at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Northern_Saw-whet_Owl/id

Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on 6 August 2018 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/northern-saw-whet-owl

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International. 2016. Aegolius acadicus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22689366A93228694. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22689366A93228694.en. Downloaded on 06 August 2018.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501. Downloaded on 6 August 2018 at: http://ak.audubon.org/conservation/alaska-watchlist

It’s a Great Day to Bird

Kachemak Bay Birder Carol Harding introduces us to our largest Songbird – the Common Raven and the KBB September Bird of the Month. Learn more about this fascinating bird which makes its home year-round in Homer, Alaska.

Yes. Hummingbirds can be found in Homer during the summer, and occasionally the tenacious little birds stick around for the winter too. To learn more about these fascinating little birds, check out the story “Hummers in Homer” by Kachemak Bay Birder, Lani Raymond (published September 12, 2018)

Common Raven

(Corvus corax)

(Photo by Robin Edwards)

General Information: Other than commonly seen, there is nothing ‘common’ about the Common Raven – a member of the Corvidae Family, Order Passeriformes (yes a “songbird”). There are eight subspecies of Raven, with the Common Raven of Alaska sharing the Corvidae Family spotlight with the Northwestern Crow, Gray Jay, Steller’s Jay, and Black-billed Magpie of Homer.

The raven is often described as the ‘Einstein of birds’—exhibiting unique problem-solving abilities and the ability to learn from observed behavior. The brain of a Common Raven is among the largest of all birds. And, as if the bird knows it is special and not common, the walk of a raven has been described as a swagger accentuated with a couple of hops as distinguished from the waddling crow.

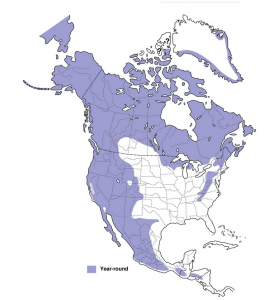

Range:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Raven/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: The Common Raven is a large bird, with glossy black feathers, a large bill, shaggy throat feathers, weighing in at 2.6 pounds, and 25 inches long – not your average Passerine song bird. Juvenile birds lack the shaggy throat feathers.

They are larger than the Northwestern Crow as demonstrated in the photo below. A good way to distinguish a Common Raven from an American or Northwestern Crow is the by their wedge-shaped tails, best observed in flight. They are long-lived birds.

Northwestern Crow in the foreground, Common Raven in the background

Photo by Randy Weisser

Preferred Habitat: The Common Raven is often distinguished from the Northwestern Crow by habitat selection with the Raven preferring more open countryside areas near forested areas whereas the crow is more habituated to human presence. However, being an exceptional bird, the raven provides an exception to the rule and is often found on Homer beaches with the reward of a good food supply and open space.

The Raven is adaptable to a wide variety of habitat — at home in the Alaskan Arctic, forest, grassland, and coast. And, for you ‘snowbirds,’ the Common Raven is even found in the Southwestern, ‘lower 48’, desert.

Breeding Season: Ravens mate for life. In interior Alaska, mating behavior is displayed in mid-January with nesting beginning in mid-March.

Nesting: Nests are large – essentially a pile of sticks, up to five feet in diameter and two feet in height, forming a platform of weaved sticks, and often found in the crouch of a tree or cliff overhang. The male will salvage sticks or even break off tree limbs three-foot long to contribute to the nest. The female is the interior designer making an inner cup 5-6 inches deep and 9-12 inches wide. They generally pick a new nesting area each year.

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Eggs and Incubation: The female lays 3-7 eggs with an incubation period of 20-25 days. The female incubates while the male brings food to the female. The pair has one brood a year.

The chicks are altricial – blind and featherless, thus helpless. They are ‘nest-bound’ and require the care and feeding by both parents.

Fledging: The chicks leave the nest about 4 weeks after hatching. The remain with the parents after they fledge.

Food Preferences: The Common Raven has been described as ‘feeding on practically anything’ in its Omnivore style dietary preferences. They are opportunistic feeders.

The Common Raven is often a major predator, especially taking nest eggs of seabirds. Foraging is often facilitated by a pair of Ravens as they incorporate clever methods of finding food.

They will cache or hide their food, and raid other ravens’ caches. They are known to regurgitate undigestable food (think pellets). Their diet is mostly small mammals, but also berries and other fruit, grains, small invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles (outside of Alaska, of course), and birds.

They will follow a predator’s tracks to a fresh kill; and will tug on the tail feathers of a raptor (such as Bald Eagle) to distract it so it can steal a bite of food. This activity has been observed on the beach at Anchor Point during the summer fishing season. Check it out next time you are there.

During the non-breeding season, they may travel up to 30-40 miles from their roost site to feed.

Roosting: In winter, Common Ravens may gather in flocks to forage during the day and to roost at night. During the rest of the year, they are often coupled, or in small groups. As many as 800 ravens have been seen in one roost near Fairbanks. Now that is a lot of ravens.

Migration: The Common Raven is a year-round resident of Homer – well throughout its range. It has been the only bird present during the Christmas Bird Count in Barrow.

Vocalizations: The Common Raven is described as a great mimic and possesses a varied repertoire of social vocalizations. One study in Alaska showed ravens have more than 30 distinct vocalizations (including mews, whistles, even dripping water sounds). The most common vocalization is deep guttural or croaking voice – it almost sounds like the Raven is talking to you, or voicing an opinion. They are talented mimics.

Call: cr-r-r-ruck

Flight Call: Kaw

Fun Facts (there are a lot of them for the raven):

Conservation Status: Ravens disappeared from much of the East and Midwest before 1900. In recent decades they have been expanding their range again, especially in the northeast, spreading south into formerly occupied areas.

The International Union of Conservation of Nature lists the Common Raven as a species of Least Concern – trend increasing. The raven does not appear on the Alaska Audubon’s Alaska Watchlist 2017. There is an estimated 7.7 million Common Ravens.

Other Raven Species in Alaska: There are no other raven species in Alaska, but other members of the corvid family here include the Northwestern Crow, Steller’s Jay, Gray Jay, and Black-billed Magpie.

For more information: The Common Raven has been researched extensively. Several good books include:

The National Audubon Society has a great video on ravens singing to their mates. Check it out at: http://www.audubon.org/news/listen-sweet-soft-warble-common-ravens-sing-their-partners

Sources of Information:

Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Downloaded on 11 August 2018 at http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=commonraven.main

American Bird Conservancy. Downloaded on 11 August 2018 at https://abcbirds.org/bird/common-raven/

Arnold B. van den Berg/Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds: Common Raven. Downloaded on 16 May 2018 https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Common_Raven/id

Marzluff, John M. and Tony Angell. 2005. In the Company of Crows and Ravens. Yale University.

National Audubon, Guide to Birds of North America. Downloaded on 11 April 2018. http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/common-raven

National Georgraphic Society. Downloaded on 11 August 2018 at: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birds/c/common-raven/

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-3. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 16 May 2018.

Sibley, David Allen. 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. Alfred A. Knopf. New York.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501. Downloaded on 11 April 2018.

William W.H. Gunn//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

Our August Bird Rhythms presentation on KBBI features the Marbled Murrelet – our Bird of the Month, plus Louise Ashmun what to do if you find a bird with a deformed beak or an injured bird (see our “Home” page for who to contact). The presentation also addresses what to do for our safety as we live in bear country – alternatives to feeding birds year-round.

Carla Stanley talks about the importance of bird habitat for food, water, shelter, and nesting areas to hatch and raise their young. She also talks about the Kachemak Bay Birders’ Bird of the Month – the Arctic Tern. To learn more about the Arctic Tern go to: http://kachemakbaybirders.org/blog/category/bird-of-the-month/ (Be sure to scroll down to reach the Arctic Tern post).

Most of us have had birds strike/collide with the windows at our home. We are disheartened by the death or injury of birds when this happens. But what can we do? Kachemak Bay Birder, Michelle Michaud lets us know in her recent Homer News article: https://www.homernews.com/opinion/what-just-hit-my-window/.

Find out what you can do, and what others have done, to prevent these window strikes/collisions.

Photos by Michelle Michaud

Read the Homer News article by Kachemak Bay Birder Michelle Michaud about the importance of keeping cats indoors.

http://homernews.com/2018-07-19/point-view-no-cat-left-outdoors

Marbled Murrelet

(Brachyramphus marmoratus)

Photo by Michelle Michaud – Winter Plumage

Photo by Michelle Michaud – Winter Plumage

General Information: The Marbled Murrelet is small chunky, long-lived seabird. This bird is unique among aclids, including other murrelets, in that it nests high up in large coastal trees. In the Pacific Northwest, these species can be found nesting up to 50 miles inland in old-growth forests. The species has a global population of 385,000, with 70% of the population residing in Alaska. It is a member of the alcidae family.

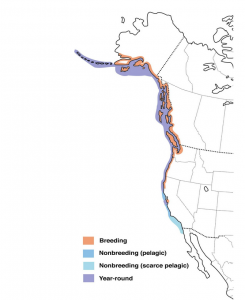

Range: The Marbled Murrelet can be found along the Pacific coast from northern Baja California out into the Aleutian Islands. This chunky little seabird can be found year-round in Kachemak Bay and Cook Inlet.

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Marbled_Murrelet/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: Often found in pairs, but in protected bays in Alaska, the Marbled Murrelet can be found in groups numbering around 50 birds. In breeding plumage darkish-brown overall. In non-breeding plumage a black cap and cheep patch, white collar, white scapulars, white breast and vent. Fairly long bill.

They forage, loaf, molt, preen, and undertake courtship displays in near-shore marine waters.

Preferred Habitat: This bird spends all of its time on the ocean, except when breeding. Winters at sea.

Breeding Season: April through September

Nests: Moss-covered platforms on large moss-covered limbs in old-growth trees (200+ years old). In treeless areas in Alaska, the bird nests on the ground or in rocky cavities typically within one-mile of shore, but no more than four-miles from shore.

Eggs and Incubation: Egg laying begins in April through late June/early July. Only one egg is laid. Nestlings are semi-precocial and downy. The nest is tended by both parents and hatchlings are brooded up to three days (birds stay in the nest).

Fledging: The chick leaves the nest 27-28 days following hatching, flying either to sea or a lake near the coast.

Food Preferences: Marbled Murrelets are opportunistic feeders, consuming small fish (e.g, Sand Lance, Capelin, Herring) and crustaceans (Shrimp, Mysids, Euphausiids, and Amphipods).

Feeding Methodology: Surface diver, foraging in shallow water (100 feet or less). Uses it wings to swim under water to catch fish. Prefers waters at the mouth of rivers and glacial streams, however, it can be found foraging 30 miles out from shore.

Migration: Some birds move south in the winter.

Vocalizations: Call is a high, gull-like squeal. At dusk a clear “keer, keer, keer” call.

Threats: Habitat loss is the primary threat in the lower 48, where more than 95% of its habitat has been logged. In Alaska, threats include changes in food availability, avian predators, incidental by-catch in gillnet fisheries, and loss of habitat through old-growth logging. Marbled Murrelets are vulnerable to oil and marine pollution.

Fun Facts:

Conservation Status: This species is declining and along the Pacific Coast (California, Oregon, and Washington), the species is listed a threatened under the Endangered Species Act. In Alaska, the Marbled Murrelet is on the Alaska Audubon “Alaska Watchlist 2017 – Red List”. Species on the “red list” are either have declining or depressed population trends. Although the Marble Murrelet has declined in population, it population has stabilized over the past decade.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the Marbled Murrelet as endangered; its population trend decreasing.

Similar Species in Alaska: In the Alaska, other murrelet species include the Kittletz Murrelet and the Ancient Murrelet. Occasionally, the Long-billed Murrelet strays into Alaskan waters, including Kachemak Bay (this bird breeds in Siberia).

Sources of Information:

Audubon, Guide to Birds of North America. Downloaded on 11 April 2018. www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/marbled-murrelet

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds – Marbled Murrelet. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Marbled_Murrelet/overview Downloaded on 11 April 2018.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Hank Lentfer//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab

International Union for Conservation of Nature. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017-3. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 11 April 2018.

Sibley, David Allen. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Andrew Stewart Publishing Inc.

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Southwest Region, Arcata Office. Marbled Murrelet Species Profile. Downloaded on 30 July 2018 at https://www.fws.gov/arcata/es/birds/mm/m_murrelet.html

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501. Downloaded on 11 April 2018.