Long-tailed Duck

(Clangula hyemalis)

General Information: Formerly known as Old Squaw, this duck is a circumpolar breeder and a common winter resident in Kachemak Bay off the Homer Spit. The “old squaw” name was in reference to the bird’s talkative behavior, although it is the male Long-tailed Duck that “talks” the most.

The Long-tailed Duck is a member of the Anatidae family, and the only living member of the genus Clangula.

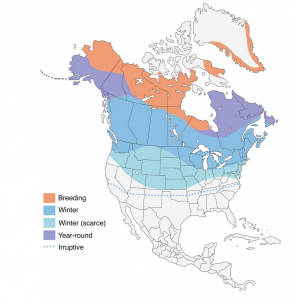

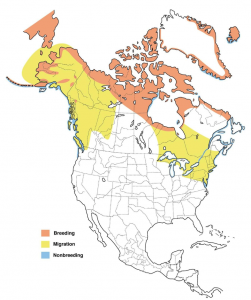

Range: You will have to travel north to find these birds – summer or winter. In North America they winter in the northern portions of the eastern U.S., Alaska, and Canada, and breed in the Alaska, northern Canada, and the Soviet Union.

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Long-tailed_Duck/maps-range

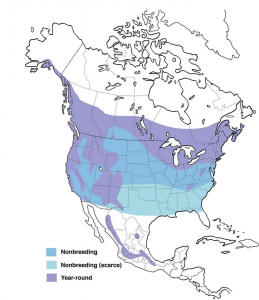

Worldwide Range

Source: http://maps.iucnredlist.org/map.html?id=22680427

Bird Biology:

Characteristics/Description: The summer breeding plumage is distinctively different from the winter plumage. In summer, males have a black head, chest, and wings with a gray face patch that surrounds the eyes. The male’s upper back feathers are long and buffy with black centers. The central tail feather very long (hence their name). The male’s winter plumage, displays a white head and neck, but the gray face patch remains. The winter plumage also includes large black spots extending from the side of the check down through the side of the neck. There is a black band across the breast and lower neck. Their lower back is black. The upper back feathers are long and gray. The central tail feather is black. Eyes are a dull yellow-brown.

Females in the summer have mostly a dark head and heck, with a white patch around the eyes, extending in a thin line towards the ears. Back and breast are various shades of gray or brown. Eyes are brown. During the winter, their head and neck are white with a round dark brown cheek patch. They have a white belly. Their crown, breast, and back are brownish-gray.

Both sexes have uniformly dark under-wings, and small bodies with large heads. They sit low in the water and are often hidden by the ocean waves.

Preferred Habitat: During the breeding season, lakes and ponds are preferred. During the winter, they prefer the open ocean and can also be found on large freshwater lakes. A good spot to find them in Kachemak Bay is off the end of the Homer Spit.

Breeding Season: Breeds in the northern Arctic boreal forest and tundra, utilizing open permafrost pools and lake islands. The breeding season begins in late May in the south, to June in the north. They have a single brood.

Nest: The nest is a shallow scrape on the ground (often islands or peninsulas), lined with nearby plant material (e.g., willow and/or birch leaves), down, and feathers. The nests are placed close to the water. These birds are sociable nesters, nesting near other Long-tailed Ducks.

Eggs and Incubation: Usually 5-9 eggs constitute a clutch. The female incubates the eggs for 23-25 days. The chicks are born precocial (eyes open) and downy. The young are lead to sea shortly after hatching. They are able to swim, dive, and feed themselves immediately.

Fledging: The hatchlings become independent approximately 5 weeks after hatching.

Food Preferences: Long-tailed ducks eat aquatic invertebrates – crustaceans (e.g., amphipods and cladocerans), mollusks, fish, and other marine invertebrates. During the breeding season, they will also eat freshwater insects and insect larvae, plant material (algae, grasses, seeds, and fruits of tundra plants).

Feeding Methodology: Long-tailed ducks are “diving” ducks.

Migration: The Long-tailed Duck migrates from its breeding ground in the far north to its wintering grounds in the not so far north. Spring migration to the breeding grounds begins late February through May, and fall migration to the wintering grounds begins in October continuing through December. The migration is often in groups, and the birds fly low over the water.

Vocalizations: These birds are active vocalizers all year long. Their call is a three-part yodel.

Threats: These birds are “sea” birds and are susceptible to by-catch in gill nets, and oil pollution.

Fun Facts:

- This bird can dive 200 feet, although most food is obtained within the first 30 feet of the surface. One of the deepest diving ducks in the world.

- A diving duck, it spends more time underwater than it does on top of the water.

- Adults molt three times per year, rather than the typical two times per year of other ducks.

- And that beautiful plumage we see during the winter? That is actually their breeding plumage (attracting a mate), although the birds actual breed during the spring where their plumage is non-breeding plumage. Confusing right?

Conservation Status: The world population is estimated at between 3.2 million and 3.75 million birds.

The International Union of Concerned Scientists list the Long-tailed Duck as vulnerable due to the severe wintering population decline in the Baltic Sea between the early 1990s and late 2000.

The Alaska Audubon Society has identified the Long-tailed Duck as a species in possible decline on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, although stable on the Alaska Coastal Plain (Audubon Alaska Watchlist 2017: Common Species Suspected to be Declining).

Similar Species: Harlequin Duck, Northern Pintail, Steller’s Eider.

Sources of Information:

All About Birds. 2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Downloaded on 29 July 2018. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Long-tailed_Duck/id

Audubon: Guide to North American Birds. Downloaded on 30 July 2018 at https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/long-tailed-duck.

Baicich, Paul J. and Colin J.O. Harrison. 19997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International. 2018. Clangula hyemalis (amended version of 2017 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22680427A122303234. Downloaded on 29 July 2018.

Dunn, Jon L. and Jonathan Alderer, Editors. National Geographic: Field Guide to Birds of North America. 5th Edition, 2nd Printing. 2008.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Henri Ouellet//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab (ML Audio 74469)

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.