Gary Lyon, Kachemak Bay Birder, describes our Bird of the Month for May – the Townsend’s Warbler. The Townsend’s Warbler is the only one of eight warblers found in Alaska. Listen to the Bird Rhythms audio to learn more about the Townsend’s Warbler, and what the other seven warblers are found in Alaska during the breeding season.

June 2019 Bird of the Month – Merlin

Merlin

(Falco columbarius)

General Information: The Merlin is “pigeon” size, which is why it might also be known as the “pigeon hawk.” This small raptor, known for its speed, is a member of the falcon (Falconidae) family.

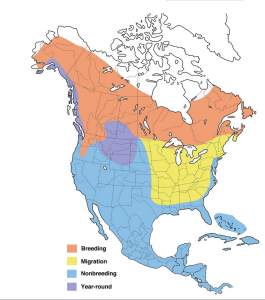

North America Range

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Merlin/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: This small falcon has a large head, stocky body, sharply pointed wings, wings are sharply pointed. Males are slaty-gray to dark gray, while female and immature birds are browner. The chest is heavily streaked, the underwings are dark. The tail sports narrow white bands. The falcon’s face lacks the “mustache” strip or malar depicted on American Kestrels or Peregrine Falcons. Some think their expression is mean looking.

These birds are between 9.4 and 11.8 inches in length, weigh in between 5.6 and 8.5 ounces, and have a wingspan of 20.9 to 26.8 inches. Females are larger than the males. Size wise, they are between a robin and a crow.

The Merlin is generally solitary during the non-breeding season. This bird is stealthy and does not hover, like an American Kestrel. Its flight is fast (typically 30+ miles per hour) and direct, seeming to appear out of nowhere, flying with rapid wing-beats, unlike the Sharp-shinned Hawk which has a flap, flap, glide motion.

Preferred Habitat: Open and semi-open habitat – prairies; open or broken coniferous forests; rivers and bogs in forest, tundra, alpine tundra; coastal areas; and islands on large lakes. In urbanized areas, may be found along tree-lined streets, cemeteries, and parks. You may encounter the Merlin looking for a meal at your bird feeder – the meal being an unsuspecting bird.

In the breeding season, the Merlin breeds in the forest – sparse woodlands edges, mountainous areas, or open plains/prairies with scattered trees.

Wintering habitat does not differ, although the Merlin may be frequently found in coastal areas with an abundance of shorebirds to prey upon or in open prairies with an abundance of longspurs and larks.

Breeding Season: Begins early to mid May, ending early July.

The Merlin performs flight displays to attract a female. These displays include strong bursts of level flight, while rocking side to side; broad U-shaped dives; and slow, fluttering flights in a circle or figure-eight when near a perched mate. The male will make a slow landing keeping its legs outstretched, head bowed, and tail fanned. And what female can resist and male who brings her food?

Nest: The Merlin utilizes old tree nests of other birds (e.g., corvids and hawks) . Sometimes they may use an open tree cavity, cliff-ledges, rocky hillsides, and even find a suitable nesting spot on the ground. When nesting in a tree, the nest is generally 15-35 feet above the ground, but may be as high up as 60 feet. If on the ground, the bird will line the nest with plant material pulled in while the bird is on the nest. They rarely reuse the same nest. The Merlin is highly territorial during the nesting season and will chase off other Merlins.

Eggs and Incubation: Lays 5-6 eggs. The eggs are laid at two-day intervals. Single brood. The female begins incubation of the egg, before completing the clutch (i.e., before all the eggs are laid). The male brings food to the female during incubation. Incubation last 28-32 days.

Nestling Period: The nestlings are born altricial (naked, but downy). The young are closely brooded by the female, with the male bringing prey, but not feeding the young. Later both parents hunt to feed the growing chicks.

Fledging: The young have their feathers fully developed by 18 days, but do not fly until 25-30 days after hatching. The youngsters remain near and under the care of their parents for another six weeks before striking out on their own.

Food Preferences: Primarily small birds, but also insects and small mammals.

Feeding Methodology: The Merlin is a perch-hunting raptor, however you will rarely, if ever, see it perched on a wire. The Merlin is a master of stealth, its attack is fast and direct. This bird likes to hunt flocking species. It will consume its insect prey on the wing (in-flight) and with non-insect prey, it will find a perch in order to pluck and consume. Young Merlin will target dragonflies – maybe they like the challenge? You may find the Merlin perched for long periods of time while it scans for unsuspecting prey.

During Homer’s Shorebird Festival in May, you can generally find a Merlin on the Homer Spit in search of shorebirds such as Sandpipers and Dunlin. The Merlin attacks at high speed, coming in horizontally or from below the horizon. They generally chase their prey until the prey tires.

Migration: The Merlin is a long-distance migrant except for the dark-morph Merlin that resides in the Pacific Northwest, which live their year-round or migrate short distances following a food source. The northern prairie Merlin generally migrates to the southern and central U.S. and northern Mexico. Our Alaskan Merlin (the taiga form) migrates to the coastal and southern U.S., and may even travel as far south as Ecuador.

Spring migration is mid-February to mid-May. Winter migration is late July to mid-November, peaking in mid-September to late-October.

Vocalizations:

Call: Rapid shrill or chatter – “keh, keh, Keh, Keh, keh, keh

Fun Facts:

- This bird was formerly known as the “pigeon” hawk.

- Also known as the “little blue corporal” or “bullet hawk”

Conservation Status: The Merlin suffered widespread declines in the 1960s due to pesticide contamination. However, with the removal of pesticides such as DDT from use in the United States, the Merlin population is now considered stable.

The International Union of Conservation of Nature has listed the Merlin as a species of Least Concern, with an estimated worldwide population between 0.5 million and 2.0 million.

The Merlin is not on the Alaska Audubon’s “Alaska Watchlist” for 2017. The National Audubon Society considers the Merlin to be climate endangered.

Threats: While the species population is currently stable, threats to the species include habitat loss from agriculture (farming and ranching), threats from energy production (wind turbines, fracking), transportation (utility and service lines, cell towers), human disturbance (recreational activities), pollution (ag and forestry effluents), invasive species, and climate change.

Similar Species in Alaska: Sharp-shinned Hawk and American Kestrel

Sources of Information:

Audubon, Guide to Birds of North American. Downloaded on May 16, 2019 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/merlin

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides

BirdLife International 2016. Falco columbarius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22696453A93562971. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22696453A93562971.en. Downloaded on 16 May 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. 2017. Downloaded on 16 May 2019 at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Merlin/id

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

National Audubon Society. Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.

2019 Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival Summary

Preliminary Shorebird Festival Summary and some great stories!!

Sunday morning during the Festival event at the lower platform at the end of the FAA Rd, a lynx crossed above the end of Beluga Lake heading toward the platform at the end of the Calvin and Coyle trail! A wonderful opportunity for folks to see a lynx–no one remembers ever seeing a lynx there before in spite of many wildlife viewers in that area over the years. (I am going to attach the video I was sent. I believe this was taken by Lisle Gwynn. I also do not have permission to send it so am on shaky ground there also. It is such a fantastic glimpse of wildlife right here in Homer! If someone else took it, please let me know and I will send out a correction.)

On previous days in that same area, a nesting TRUMPETER SWAN was seen chasing off groups of geese that rest in that area. On four occasions it was reported that the swan would chase the group of geese up into the air and then target one goose to follow. One version of a chase on Saturday said the swan was maybe five feet behind the goose for several circles above the lake, getting closer and closer (the swan with his mouth open at times), seemingly snapping at the tailfeathers of the goose, he said! Usually the chase then went out of sight, the swan returning a while later… and the goose? Some other birder might have seen what happened there or we’ll never know.

It seems interesting that there is a pair of nesting SONG SPARROWS on the top of Gull Island. Never been reported before. (Spit real estate at a premium, perhaps?)

There were 124 species seen during the four days of the Festival. There are still some reports trickling in, so this number may go up. Last minute additions: HORNED LARKS near the Harbor and POMARINE JAEGER and SOOTY SHERWATER at the Anchor River. Overall, there was only one warbler (YELLOW-RUMPED) seen and one owl (GREAT HORNED); no flycatchers, no eiders. A highlight for many was seeing several CASPIAN TERNS on Saturday in the Mud Bay/Lighthouse Village Platform area.

Loading...

Loading...

May 2019 Bird of the Month

Townsend’s Warbler

(Setophaga townsendi)

General Information

The Townsend’s Warbler is a small, colorful, black, white, and yellow songbird found in and around Homer during its breeding season. This species is member of the wood warblers in the family Parulidae, genus Setophaga. There are 53 species of wood warblers that occur in North America.

The Townsend’s Warbler is named for John Kirk Townsend, an American naturalist, ornithologist, and collector. Townsend fell ill and died from the effects of powered arsenic used to prepare bird skins. The Townsend’s Solitaire (a Thrush) is also named for him.

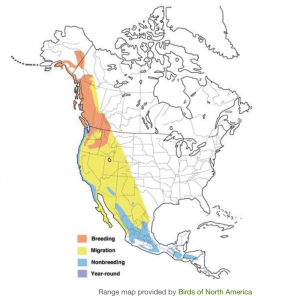

Range: The Townsend’s Warbler is a west coast warbler species, breeding in Alaska, Canada, and the Pacific Northwest. This species spends its winter along the west coast from Washington to northern Baja, southern Arizona, trans-Pecos Texas, and Central America.

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Townsends_Warbler/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: The Townsend’s Warbler is about 5 inches in length and weighs in at 0.31 oz (8.8 grams). The bird has a bright yellow breast, golden olive cheeks, and gray wings. The male has a black cap, distinct “zorro” mask, black throat, and is streaked black down its sides.

Preferred Habitat: In the breeding season, this warbler can be found in coniferous and mixed deciduous-coniferous forests. In its northern range, it prefers the White Spruce forest. In the winter, these birds also can be found in oaks, madrones, laurels.

A good place to see a Townsend’s Warbler in the Homer area is along the Calvin and Coyle Trail.

Breeding Season: Breeding occurs from late May to early June. The pair form a seasonal pair bond – so a new mate each year. The male is very territorial while on the breeding grounds. This warbler reaches sexual maturity at one-year of age and can begin breeding.

Nest: The nest is a large, compact cup-shaped nest made out of bark, conifer needles, lichens, moss, slender twigs, and dried grasses. The nest is then lined with moss, hair, and fine grasses. The well-concealed nest is built in a conifer tree well out on a horizontal branch. Both sexes are believed to construct the nest.

Eggs and Incubation: Three to seven eggs are laid and incubated for 12 days. Not much is known about incubation, but it is believed that both parents incubate the eggs.

Fledging: The chicks are fed by the female, and possibly by the male. They fledge 8-10 days following hatching.

Food Preferences: Townsend’s Warblers are primarily insectivores – preferring caterpillars, true bugs, and beetles. They may also supplement their diet with a few spiders, seeds, and plant galls.

On the wintering grounds in Mexico, the Townsend’s Warbler feasts on the sugary excretions of scale insects. Yum!!! It loves this food source enough to defend its territories around trees infested with these insects.

Feeding Methodology: Townsend’s Warblers forage in the top 1/3 of a tree by gleening, hawking, and hovering to capture their prey. In the non-breeding season, they will feed in mixed flocks.

Migration: The birds beginning heading north to their breeding grounds (spring migration) in early April through late May, with birds returning to their wintering grounds beginning early August through October. They are often found in mixed flocks during migration.

Vocalizations:

Song: “zoo, zoo, zoo zee” or “weezy, weezy, weezy, weeZEE”

Call: Sharp “tsik” or “chip”

Flight Call: Clear “swit”

Threats: The primary threat is loss of habitat, pesticides, and climate change. To see how climate change is predicted to affect the Townsend’s Warbler between 2000 and 2080, go the bottom of the page at: http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/townsends-warbler

Fun Facts:

- Males begin singing prior to leaving their wintering grounds.

- Females may partially construct a nest in one tree, then move all the materials to another tree, finishing the nest there.

Conservation Status: The global population is estimated at around 17 million. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the species as “least concern” with a stable population. The National Audubon Society considers the Townsend’s Warbler a “climate threatened” species, although the species is still common and widespread. This species is not on the Alaska Audubon’s Alaska Watchlist.

Common Warbler Species in Alaska: Other warbler species in Alaska includes the Yellow Warbler, Yellow-rumped Warbler, Blackpoll Warbler, Arctic Warbler, Wilson’s Warbler, Orange-crowned Warbler, and the Northern Waterthrush.

Sources of Information

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International 2016. Setophaga townsendi. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22721683A94723311. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22721683A94723311.en. Downloaded on 14 April 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds – Townsend’s Warbler. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Townsends_Warbler/overview Downloaded on 13 April 2019.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

National Audubon Society. 2018. http://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/townsends-warbler. Downloaded on 13 April 2019.

Sibley, David Allen. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. Andrew Steward Publishing.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Audubon Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501

It’s a Great Day to Bird

Bird Rhythms – March 2019

Carol Ford introduces her audience to the Glaucous-winged Gull, Kachemak Bay Birders “Bird of the Month”. She also describes a wandering fall visitor to the Homer area – the Bohemian Waxwing. Learn how this bird got its name and what it likes to eat while visiting the Cosmic Hamlet by the Sea.

Varied Thrush – April Bird of the Month – 2019

Varied Thrush

Photo by Robin Edwards

General Information: The Varied Thrush (Ixoreus naevius), a forest loving, secretive bird, is quite common – often heard but not easily observed. It is a member of the Turdidae family (thrushes). The Varied Thrush’s haunting song is generally first heard and welcomed by local Homer area residents in late March or early April as it announces the oncoming, long-awaited, spring season.

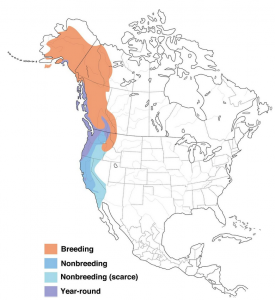

Range:

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Varied_Thrush/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: When fortunate to be seen, it is not easy to miss this bird with its distinctive plumage: bold black, blue-gray, and orange. Look for an orange eyebrow, wide black collar, orange underparts, blue-gray back and tail, and orange wing-bars. The female and juvenile are similar in color to the male, but duller and generally lacking the wide black v-shaped collar. This bird is about the same size as the American Robin, but stockier.

Due to its habitat preference of heavy forest understory, the bird is not readily observed. Be patient. Follow its song and listen for its foraging behavior as it busily scratching the forest floor duff.

Preferred Habitat: This bird’s preferred habitat is the dense, mature, unfragmented moist coniferous forest (fir, hemlock, spruce, with a dense understory). It may also be found in Alder thickets and Aspen groves. In the winter, it is often more visible as it frequents parks, gardens, oak woodlands, ravines, and riparian areas.

Don’t forget to look up, as these birds can sometimes be found singing at tree tops (dead or alive), often perched for extended periods of time as they throw their heads back and vocalize the presence of their territory.

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Breeding Season: The breeding season begins in mid-April for those birds in the southern portion of the bird’s breeding range, and in mid-May for those birds located further north – like our birds in Alaska.

Nest: The male sings to defend its territory, generally active at dawn and dusk. However, the female is believed to choose the nest site. Nests are built utilizing tree branches, with nests located 4-20 feet up, but close to the trunk; generally, in a small conifer.

The female gathers the materials for the open cup nest. The outer layer of the nest is composed of twigs, bark strips, mosses, weeds, and grasses. A layer of rotten wood, moss, mud, or decomposing grasses is then added and allowed to harden the cup. A final nesting layer is composed of fine grasses, dead leaves, and fine moss. The moss is generally draped over the rim and placed on the outside of the nest.

Eggs and Incubation: Generally, three-four eggs, but as many as six and as few as one are laid. The pair may have a double brood. The female alone sits on the eggs for 12 days. Chicks are altricial (eyes closed, downy, and unable to feed themselves). The chicks are tended by both parents.

Fledging: It is estimated the chicks fledge 13-15 days following hatching, however, not a lot is known about child rearing and fledging for Varied Thrush chicks.

Food Preferences: In the breeding season, the Varied Thrush utilizes protein sources such as insects and arthropods found in the leaf litter, including beetles, ants, caterpillars, sowbugs, snails, earthworms, and spiders. In winter, when insects are few, dried fruits, seeds, and nuts make up their diet.

Feeding Methodology: The Varied Thrush forages on the ground, moving dead leaves with a sweeping motion of their bill and then quickly hopping backwards to clear a spot with their feet before checking out their prey. This bird may also forage in low bushes (generally during the winter). This thrush is generally a solitary bird, but in the fall and winter, they may form loose flocks around a good food source. I recently saw seven Varied Thrushes feeding in a state park campground on the northern coast of Oregon.

Photos by Michelle Michaud

Migration: Spring migration is mid-March to mid-May, while fall migration is from late August to late November. In the winter, many Alaskan birds migrate to the west coast – south Kenai Peninsula of Alaska to southern California.

Vocalizations:

Song: A haunting sound – “eeeeeeeee” (pause) “errrrrrr”.

Call: Low “churk” or “chup”

To many this bird’s song sounds like fingernails being run down a chalk board.

Threats: Like many birds, loss of forest habitat due to habitat fragmentation and logging is a significant threat. The best conservation strategy is to retain habitat patches of 40-acres or more with habitat connections. Varied Thrushes living around human habitation are subject to window strikes, predation by outdoor cats (domestic and feral), and car collisions.

Fun Facts:

- Varied Thrush populations are cyclical, with fluctuations on a 2-year cycle.

Conservation Status: The Varied Thrush is fairly common. However, populations have declined over 2.5% per year since 1966. The current global breeding population is estimated at 20 million.

The Varied Thrush does not appear on the Audubon Alaska’s “Watchlist”; and is listed as a species of “least” concern by the International Union of Concerned Scientists (IUCN). The IUCN does note the species population is declining.

The National Audubon Society lists the Varied Thrush as a priority bird: climate endangered.

Similar Species in Alaska: American Robin

Sources of Information:

All About Birds. 2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Downloaded on 13 August 2018 at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Varied_Thrush/id

Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on 13 August 2018 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/varied-thrush

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International. 2016. Ixoreus naevius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22708385A94159470. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22708385A94159470.en. Downloaded on 13 August 2018.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501. Downloaded on 13 August 2018 at: http://ak.audubon.org/conservation/alaska-watchlist

It’s a Great Day to Bird

Glaucous-Winged Gull – March 2019 Bird of the Month

Photo by Michelle Michaud

General Information: The Glaucous-winged Gull (Larus glaucescens) is a common west coast breeder and winter resident found year-round in on the Kenai Peninsula. No sexual dimorphism here – both male and female look alike. They are members of the Order: Charadriiformes (which includes Shorebirds), Family: Laridae (Gulls and Terns)

North America Range

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Glaucous-winged_Gull/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: All ages have pink legs – a good field ID. From there it becomes more difficult as this gull doesn’t reach adult plumage until its fourth year. And, to add to the confusion, there are the breeding and non-breeding plumages (although not that much different). A good field bird book is needed if you want to be familiar with gulls.

Glaucous-winged Gulls are large, ranging in size from 19 -23 inches, and weighing in at around 2.0-2.5 pounds, slightly larger than a Herring Gull, but slightly smaller than a Glaucous Gull.

Adults: Look for a large, stocky gray/silver gull with gray back and gray/silver (not black) wingtips, with white spots near tip. Eyes are dark compared to light eyes on Herring and Glaucous Gulls. Their bill is yellow with some red on lower mandible and don’t forget the pink legs. Breeding birds have an all white head and neck, while non-breeding birds have mottled gray in the head and neck. They are commonly found in pairs year-round, but will forage alone or in large groups.

Photo by Michelle Michaud

There are a number of different plumages for birds that have yet to reach sexual maturity. For a description of the different plumages go to: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Glaucous-winged_Gull/id

Photo by MIchelle Michaud

Preferred Habitat: Look for the Glaucous-winged Gull near or on coastal water year-round. It prefers good food sources such as bays, inlets, estuaries, beaches, harbors, mud flats, and spends much of the winter loafing on offshore waters and beaches.

In the breeding season, this gull nests on steep coastal cliffs and rocky offshore islands (e.g., Gull Island).

Breeding Season: Begins mid-May to early June, ending in August. Glaucous-winged Gulls do not begin breeding until their fourth year or later and breeds/nests in colonies, sometimes quite dense. As a social breeder, it may breed/nest in colonies with other gull species or seabirds (e.g., puffins, murres).

Nesting: Preference for a nest site is a nest on the ground, rock ledges, and cliffs, but they may nest on suitable buildings or structures. The pair will ‘nest bond’, generally starting several nests, but completing only one nest.

The nest is a bulky cup shape consisting of grasses, seaweed, feathers, fish bones, and other debris (including plastic, unfortunately). The use of plastic by birds is not a good use of “recycling plastic”since the plastic often be ingested or will entangle the nesting bird or chicks.

Eggs and Incubation: Typically 2-3 eggs are incubated by both parents for 26-29 days. Hatchlings are semi-precocial (eyes and ears open, but cannot move about) and downy. The chicks are fed by both parents. The chick’s coloring is cryptic to help camouflage it from predators, including other Glaucous-winged Gulls.

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Fledging: The chicks generally fledge 35-54 days following hatching and will leave the colony about two weeks later to forage on their own.

Food Preferences: Their primary food source is marine invertebrates (limpets, chitons, clams, mussels, squid, crab etc.) and fishes. They will also predate seabird eggs and chicks. They scavenge carrion and will eat food found in landfills and parking lots. Unfortunately people feed gulls, which attracts a lot of gulls in a feeding frenzy. The gulls create a riot as they swoop in to grab the morsel. This human activity is not appropriate and illegal within the City of Homer. Gulls have a notorious reputation of hanging out, in large numbers and in mixed flocks, at landfills seeking food so many birders check out landfills to see if there are any rare gulls present.

Feeding Methodology: These gulls forage at sea, in intertidal areas, along beaches, in parking lots and landfills. When on land they are ground foragers. They take prey from the surface of water or may perform a dramatic plunge into water from the air. They will try to harass and steal food from other birds, such as cormorants.

Roosting: They a social roosters with beaches a favorite roosting spot but they can also be found roosting on pilings, guardrails, lamp posts, parking lots, and in fields or dumps

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Migration: Not all Glaucous-winged Gulls migrate as many northern birds are year-round residents, moving with the food resources. For those that do migrate, spring migration is from late February to early May. Fall migration is from late August to late November. They may migrate as far south as northwestern Mexico but are rarely found inland, preferring a coastal environment.

Vocalizations: This bird’s call is a “keow” whistle. If an intruder approaches you will here the ‘ga, ga’ notes. I think that is one we’ve all heard and is most familiar.

Threats: Fishing line and hooks are deadly as Glaucous-winged Gulls are opportunistic scavengers and can ingest a hook or get entangled. So if you see fishing line and hooks on the ground, pick them up and dispose of them properly. And if you are out fishing, do not discard these items onto the ground or from your fishing boat.

Photo by Michelle Michaud

Fun Facts:

- This bird hybridizes with the Herring Gull, Western Gull, and Glaucous Gull. The young may possess physical characteristics of both parents.

- Gulls are often difficult enough to identify, especially before they reach sexual maturity, but added to that is the fact that they often inter-breed and hybridization makes field identification more difficult. Pete Dunne recommends that if you find a gull with “… a mixed array of traits, consider the very possibility that it’s a hybrid” and either try to tease out what the bird is or move on to another gull.

- This is the one of five North American Gulls that does not have black on its wing-tips.

Conservation Status:

Audubon Alaska has identified the Glaucous-winged Gull species as a common species that is declining or vulnerable, thereby warranting species conservation attention. It is estimated that 44% of the bird’s population resides in Alaska making it at-risk for climate change and other environmental influences.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) has identified the population of the Glaucous-winged Gull as increasing, with no genuine threats to the global population estimated at over 570,000 individuals.

Similar Species in Alaska: Glaucous Gull, Herring Gull

Sources of Information:

All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Downloaded on January 10, 2019 at https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Glaucous-winged_Gull/id

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International 2018. Larus glaucescens. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22694334A132543276. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22694334A132543276.en. Downloaded on 10 January 2019.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Lucas DeCicco/McCaulay Library/Cornell University Ornithology Lab (ML174609).

National Audubon Society. Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on January 10, 2019 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/glaucous-winged-gull

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501. Downloaded on January 10, 2019 at: http://ak.audubon.org/sites/g/files/amh551/f/annotated_watchlist_common_decline_2017.pdf

The gallery was not found!Rock Sandpiper – February Bird of the Month – 2019

Rock Sandpiper

(Calidris ptilocnemis)

General Information: The Rock Sandpiper is a shorebird that can be found in Cook Inlet, including on the Homer Spit during the winter. The Rock Sandpiper has a small range – Alaska, Northern Siberia, and west coast of Canada. This bird is a member of the Scolopacidae family and consists of four subspecies.

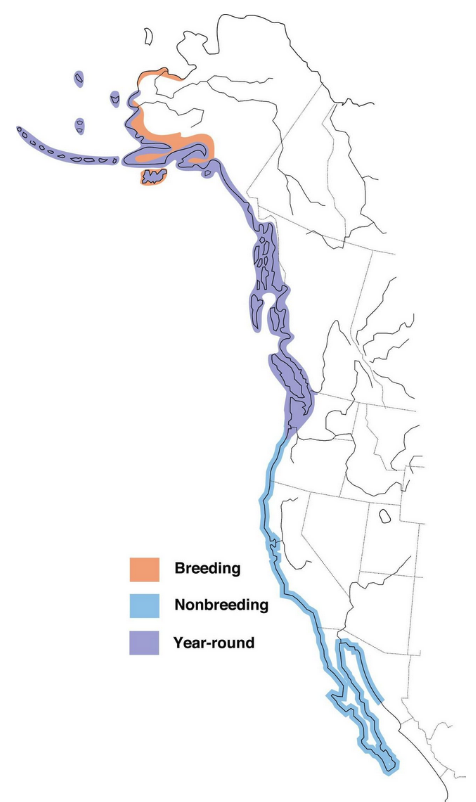

Range:

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Sandpiper/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: During the winter, this plump, medium-size shorebird is sooty gray in color, with heavily spotted white underparts. The summer plumage resembles the look of a breeding Dunlin, only messier (the black on the chest is smudged, rather than the clean margins of the black found on the Dunlin breast and belly). It has a medium-length black bill with orange at the base, and drooping slightly at the end. The bill is shorter than a Dunlin, longer than a Surfbird. The short legs are a greenish-yellow color, and it has a white wing-stripe( wing bar). Look for a dark tail in flight.

The sandpiper weighs in at 2.0-4.6 ounces, and is 7.1-9.4 inches in length. Both sexes have the same plumage – no sexual dimorphism here. Overall size wise – think American Robin.

Preferred Habitat: During the breeding season, the Rock Sandpiper breeds in low-elevation tundra areas, but may also nest at higher elevations in the mountains of western Alaska. Wintering habitat includes rocky coastlines, breakwaters, and mudflats.

Breeding Season: The breeding season begins in early June. The Rock Sandpiper is a common breeder in Alaska.

Nest: This ground nester scrapes the ground, then lines the depression with grasses, lichens, and leaves. The male begins the scrape, with the female occasionally helping to construct the lining.

Eggs and Incubation: Fur eggs are usually laid at daily intervals. Both parents incubate the eggs over approximately 20 days, with the chicks hatching at different intervals. The chicks are born precocial (leaving the nest shortly after bird and feeding on their own). The male tends the young until they fledge.

Fledging: The chicks fledge (able to fly) approximately 3 weeks following hatching.

Food Preferences: On the breeding grounds, protein is needed and the diet consists primarily of insects, but also crustaceans, mollusks, and marine worms. Supplements include berries, seeds, moss, and algae. In the winter, they utilize tidal areas and eat mostly crustaceans, insects, and small mollusks.

Feeding Methodology: In the winter the Rock Sandpiper forages in the intertidal zone (rocky coasts, mudflats, gravel beaches, sand flats, ) where it finds its food visually.

Roosting: This sandpiper roosts above the high tide line on piers, beaches, and rocky banks. It can be found roosting along the inner eastern bank of the Homer Boat Harbor during high tide in the winter months.

Migration: Spring migration is from late March to early June. Fall migration is from late June to mid-November. Peak fall migration occurs later than other shorebirds. The subspecies of Rock Sandpipers nesting on the Pribilof Islands and in the Aleutians are short-distance migrants or permanent residents. The primary Rock Sandpiper wintering in Homer is a summer resident of the Pribilofs and Aleutians.

Vocalizations: This bird is generally silent, but listen for low whistled notes sometimes vocalized in the winter.

Threats: Change of habitat due to climate change and exposure to predation. Also, while the Rock Sandpiper can be enjoyed in large numbers roosting at the Homer boat harbor and feeding at the tidal flats, winter is an energy stressor so disturbance from dogs and people is a problem.

Fun Facts:

- There are four subspecies of Rock Sandpipers with each subspecies having differing breeding plumage, but mostly look alike during the winter.

- Several subspecies winter in Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay. Several thousand wintering Rock Sandpipers can be found roosting, bathing, and preening on the northern half of the eastern bank of the Homer Boat Harbor or seen flying around the Homer Spit and landing on the tidal flats to feed. By late April the majority of the Rock Sandpiper’s have departed Homer for their breeding grounds.

- Check your photos and look carefully since small numbers of Dunlin often winter with Rock Sandpipers in Kachemak Bay, and can be confused for Rock Sandpipers (see photo above to see the difference).

- The Rock Sandpiper is closely related to the Purple Sandpiper (which resides seen on the east coast of the United States and Canada)

- Like a plover, the Rock Sandpiper may exhibit the broken wing display if a predator threatens the nest.

- A hardy bird – its wintering area often means ice on feet and legs – no problem for the Rock Sandpiper with its specialized metabolism.

Conservation Status: The estimated global population is 160,000-170,000 individuals.

The subspecies C. ptilocnemis ptilocnemis, found in the Pribilof, St. Matthews, and Hall Islands of Alaska are listed on the Alaska Audubon Watchlist 2017 Yellow List – Vulnerable Species. Species on this list are declining or vulnerable thereby warranting special conservation attention. The subspecies population status is estimated at around 20,000 birds. This subspecies primarily winters in Cook Inlet.

The International Union of Concerned Scientists have listed (Red List) the Rock Sandpiper as a species of least concern, but with a declining population.

Similar Species in Alaska: Surfbird, Dunlin, and Wandering Tattler

Marked Birds: If you see or find a Rock Sandpiper with a metal band, colored plastic leg bands, and engraved colored leg flats, please report your details to:

Dan Ruthrauff

USGS Alaska Science Center

4210 University Dr., Anchorage, Alaska, 99508

(907) 786-7162, druthrauff@usgs.gov

These birds were marked at several sites in western Alaska and are part of a distribution study.

Sources of Information:

All About Birds. 2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Downloaded on 15 August 2018 at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Sandpiper/id

Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on 15 August 2018 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/rock-sandpiper

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International. 2016. Calidris ptilocnemis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22693424A95218793. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693424A95218793.en. Downloaded on 15 August 2018.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Gill, R. E., P. S. Tomkovich, and B. J. McCaffery (2002). Rock Sandpiper (Calidris ptilocnemis), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.686. Downloaded on 15 August 2018.

Lucas DeCicco//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab (ML Audio176399).

Ruthrauff, Dan, U.S. Geological Service, Alaska Science Center. Wintering Ecology of the Rock Sandpiper. Downloaded on 15 August 2018 at: https://alaska.usgs.gov/science/biology/shorebirds/rosa_ecology.php

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.

It’s A Great Day to Bird

Bird Rhythms – January

Karin Holbook is new to birding. In this month’s Bird Rhythms, Karin shares with us her experiences as a beginning birder and how it has changed her world.

Bird Rhythms – December

Tim Quinn, local birder and member of the Kachemak Bay Birders, describes the tiny titan of local, fast moving streams – the American Dipper.