Rock Sandpiper

(Calidris ptilocnemis)

General Information: The Rock Sandpiper is a shorebird that can be found in Cook Inlet, including on the Homer Spit during the winter. The Rock Sandpiper has a small range – Alaska, Northern Siberia, and west coast of Canada. This bird is a member of the Scolopacidae family and consists of four subspecies.

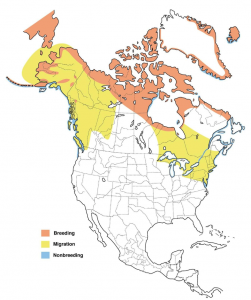

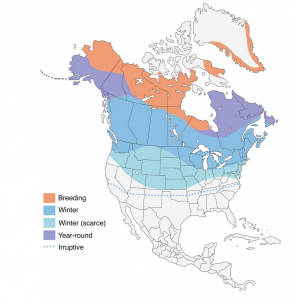

Range:

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Sandpiper/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: During the winter, this plump, medium-size shorebird is sooty gray in color, with heavily spotted white underparts. The summer plumage resembles the look of a breeding Dunlin, only messier (the black on the chest is smudged, rather than the clean margins of the black found on the Dunlin breast and belly). It has a medium-length black bill with orange at the base, and drooping slightly at the end. The bill is shorter than a Dunlin, longer than a Surfbird. The short legs are a greenish-yellow color, and it has a white wing-stripe( wing bar). Look for a dark tail in flight.

The sandpiper weighs in at 2.0-4.6 ounces, and is 7.1-9.4 inches in length. Both sexes have the same plumage – no sexual dimorphism here. Overall size wise – think American Robin.

Preferred Habitat: During the breeding season, the Rock Sandpiper breeds in low-elevation tundra areas, but may also nest at higher elevations in the mountains of western Alaska. Wintering habitat includes rocky coastlines, breakwaters, and mudflats.

Breeding Season: The breeding season begins in early June. The Rock Sandpiper is a common breeder in Alaska.

Nest: This ground nester scrapes the ground, then lines the depression with grasses, lichens, and leaves. The male begins the scrape, with the female occasionally helping to construct the lining.

Eggs and Incubation: Fur eggs are usually laid at daily intervals. Both parents incubate the eggs over approximately 20 days, with the chicks hatching at different intervals. The chicks are born precocial (leaving the nest shortly after bird and feeding on their own). The male tends the young until they fledge.

Fledging: The chicks fledge (able to fly) approximately 3 weeks following hatching.

Food Preferences: On the breeding grounds, protein is needed and the diet consists primarily of insects, but also crustaceans, mollusks, and marine worms. Supplements include berries, seeds, moss, and algae. In the winter, they utilize tidal areas and eat mostly crustaceans, insects, and small mollusks.

Feeding Methodology: In the winter the Rock Sandpiper forages in the intertidal zone (rocky coasts, mudflats, gravel beaches, sand flats, ) where it finds its food visually.

Roosting: This sandpiper roosts above the high tide line on piers, beaches, and rocky banks. It can be found roosting along the inner eastern bank of the Homer Boat Harbor during high tide in the winter months.

Migration: Spring migration is from late March to early June. Fall migration is from late June to mid-November. Peak fall migration occurs later than other shorebirds. The subspecies of Rock Sandpipers nesting on the Pribilof Islands and in the Aleutians are short-distance migrants or permanent residents. The primary Rock Sandpiper wintering in Homer is a summer resident of the Pribilofs and Aleutians.

Vocalizations: This bird is generally silent, but listen for low whistled notes sometimes vocalized in the winter.

Threats: Change of habitat due to climate change and exposure to predation. Also, while the Rock Sandpiper can be enjoyed in large numbers roosting at the Homer boat harbor and feeding at the tidal flats, winter is an energy stressor so disturbance from dogs and people is a problem.

Fun Facts:

- There are four subspecies of Rock Sandpipers with each subspecies having differing breeding plumage, but mostly look alike during the winter.

- Several subspecies winter in Cook Inlet and Kachemak Bay. Several thousand wintering Rock Sandpipers can be found roosting, bathing, and preening on the northern half of the eastern bank of the Homer Boat Harbor or seen flying around the Homer Spit and landing on the tidal flats to feed. By late April the majority of the Rock Sandpiper’s have departed Homer for their breeding grounds.

- Check your photos and look carefully since small numbers of Dunlin often winter with Rock Sandpipers in Kachemak Bay, and can be confused for Rock Sandpipers (see photo above to see the difference).

- The Rock Sandpiper is closely related to the Purple Sandpiper (which resides seen on the east coast of the United States and Canada)

- Like a plover, the Rock Sandpiper may exhibit the broken wing display if a predator threatens the nest.

- A hardy bird – its wintering area often means ice on feet and legs – no problem for the Rock Sandpiper with its specialized metabolism.

Conservation Status: The estimated global population is 160,000-170,000 individuals.

The subspecies C. ptilocnemis ptilocnemis, found in the Pribilof, St. Matthews, and Hall Islands of Alaska are listed on the Alaska Audubon Watchlist 2017 Yellow List – Vulnerable Species. Species on this list are declining or vulnerable thereby warranting special conservation attention. The subspecies population status is estimated at around 20,000 birds. This subspecies primarily winters in Cook Inlet.

The International Union of Concerned Scientists have listed (Red List) the Rock Sandpiper as a species of least concern, but with a declining population.

Similar Species in Alaska: Surfbird, Dunlin, and Wandering Tattler

Marked Birds: If you see or find a Rock Sandpiper with a metal band, colored plastic leg bands, and engraved colored leg flats, please report your details to:

Dan Ruthrauff

USGS Alaska Science Center

4210 University Dr., Anchorage, Alaska, 99508

(907) 786-7162, druthrauff@usgs.gov

These birds were marked at several sites in western Alaska and are part of a distribution study.

Sources of Information:

All About Birds. 2017. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Downloaded on 15 August 2018 at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Rock_Sandpiper/id

Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on 15 August 2018 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/rock-sandpiper

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides.

BirdLife International. 2016. Calidris ptilocnemis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22693424A95218793. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22693424A95218793.en. Downloaded on 15 August 2018.

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

Gill, R. E., P. S. Tomkovich, and B. J. McCaffery (2002). Rock Sandpiper (Calidris ptilocnemis), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.686. Downloaded on 15 August 2018.

Lucas DeCicco//Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab (ML Audio176399).

Ruthrauff, Dan, U.S. Geological Service, Alaska Science Center. Wintering Ecology of the Rock Sandpiper. Downloaded on 15 August 2018 at: https://alaska.usgs.gov/science/biology/shorebirds/rosa_ecology.php

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.

It’s A Great Day to Bird