Merlin

(Falco columbarius)

General Information: The Merlin is “pigeon” size, which is why it might also be known as the “pigeon hawk.” This small raptor, known for its speed, is a member of the falcon (Falconidae) family.

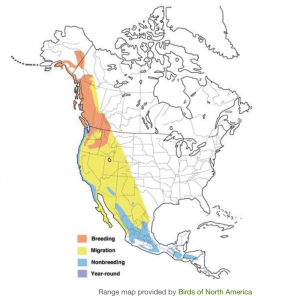

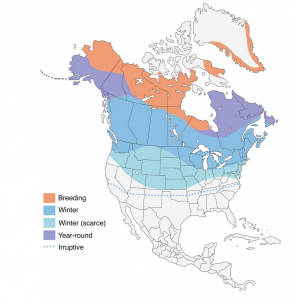

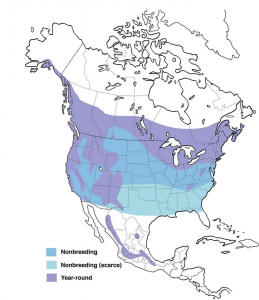

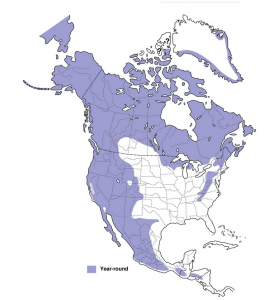

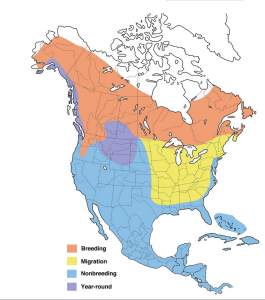

North America Range

Source: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Merlin/maps-range

Bird Biology:

Characteristics: This small falcon has a large head, stocky body, sharply pointed wings, wings are sharply pointed. Males are slaty-gray to dark gray, while female and immature birds are browner. The chest is heavily streaked, the underwings are dark. The tail sports narrow white bands. The falcon’s face lacks the “mustache” strip or malar depicted on American Kestrels or Peregrine Falcons. Some think their expression is mean looking.

These birds are between 9.4 and 11.8 inches in length, weigh in between 5.6 and 8.5 ounces, and have a wingspan of 20.9 to 26.8 inches. Females are larger than the males. Size wise, they are between a robin and a crow.

The Merlin is generally solitary during the non-breeding season. This bird is stealthy and does not hover, like an American Kestrel. Its flight is fast (typically 30+ miles per hour) and direct, seeming to appear out of nowhere, flying with rapid wing-beats, unlike the Sharp-shinned Hawk which has a flap, flap, glide motion.

Preferred Habitat: Open and semi-open habitat – prairies; open or broken coniferous forests; rivers and bogs in forest, tundra, alpine tundra; coastal areas; and islands on large lakes. In urbanized areas, may be found along tree-lined streets, cemeteries, and parks. You may encounter the Merlin looking for a meal at your bird feeder – the meal being an unsuspecting bird.

In the breeding season, the Merlin breeds in the forest – sparse woodlands edges, mountainous areas, or open plains/prairies with scattered trees.

Wintering habitat does not differ, although the Merlin may be frequently found in coastal areas with an abundance of shorebirds to prey upon or in open prairies with an abundance of longspurs and larks.

Breeding Season: Begins early to mid May, ending early July.

The Merlin performs flight displays to attract a female. These displays include strong bursts of level flight, while rocking side to side; broad U-shaped dives; and slow, fluttering flights in a circle or figure-eight when near a perched mate. The male will make a slow landing keeping its legs outstretched, head bowed, and tail fanned. And what female can resist and male who brings her food?

Nest: The Merlin utilizes old tree nests of other birds (e.g., corvids and hawks) . Sometimes they may use an open tree cavity, cliff-ledges, rocky hillsides, and even find a suitable nesting spot on the ground. When nesting in a tree, the nest is generally 15-35 feet above the ground, but may be as high up as 60 feet. If on the ground, the bird will line the nest with plant material pulled in while the bird is on the nest. They rarely reuse the same nest. The Merlin is highly territorial during the nesting season and will chase off other Merlins.

Eggs and Incubation: Lays 5-6 eggs. The eggs are laid at two-day intervals. Single brood. The female begins incubation of the egg, before completing the clutch (i.e., before all the eggs are laid). The male brings food to the female during incubation. Incubation last 28-32 days.

Nestling Period: The nestlings are born altricial (naked, but downy). The young are closely brooded by the female, with the male bringing prey, but not feeding the young. Later both parents hunt to feed the growing chicks.

Fledging: The young have their feathers fully developed by 18 days, but do not fly until 25-30 days after hatching. The youngsters remain near and under the care of their parents for another six weeks before striking out on their own.

Food Preferences: Primarily small birds, but also insects and small mammals.

Feeding Methodology: The Merlin is a perch-hunting raptor, however you will rarely, if ever, see it perched on a wire. The Merlin is a master of stealth, its attack is fast and direct. This bird likes to hunt flocking species. It will consume its insect prey on the wing (in-flight) and with non-insect prey, it will find a perch in order to pluck and consume. Young Merlin will target dragonflies – maybe they like the challenge? You may find the Merlin perched for long periods of time while it scans for unsuspecting prey.

During Homer’s Shorebird Festival in May, you can generally find a Merlin on the Homer Spit in search of shorebirds such as Sandpipers and Dunlin. The Merlin attacks at high speed, coming in horizontally or from below the horizon. They generally chase their prey until the prey tires.

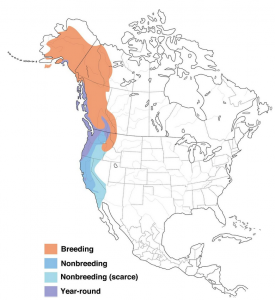

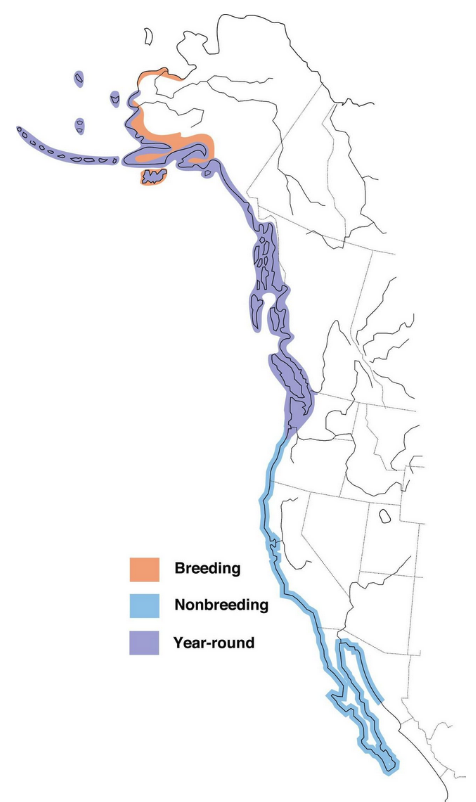

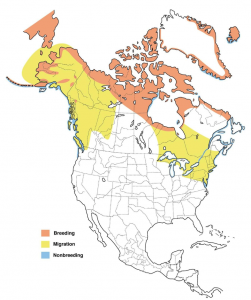

Migration: The Merlin is a long-distance migrant except for the dark-morph Merlin that resides in the Pacific Northwest, which live their year-round or migrate short distances following a food source. The northern prairie Merlin generally migrates to the southern and central U.S. and northern Mexico. Our Alaskan Merlin (the taiga form) migrates to the coastal and southern U.S., and may even travel as far south as Ecuador.

Spring migration is mid-February to mid-May. Winter migration is late July to mid-November, peaking in mid-September to late-October.

Vocalizations:

Call: Rapid shrill or chatter – “keh, keh, Keh, Keh, keh, keh

Fun Facts:

- This bird was formerly known as the “pigeon” hawk.

- Also known as the “little blue corporal” or “bullet hawk”

Conservation Status: The Merlin suffered widespread declines in the 1960s due to pesticide contamination. However, with the removal of pesticides such as DDT from use in the United States, the Merlin population is now considered stable.

The International Union of Conservation of Nature has listed the Merlin as a species of Least Concern, with an estimated worldwide population between 0.5 million and 2.0 million.

The Merlin is not on the Alaska Audubon’s “Alaska Watchlist” for 2017. The National Audubon Society considers the Merlin to be climate endangered.

Threats: While the species population is currently stable, threats to the species include habitat loss from agriculture (farming and ranching), threats from energy production (wind turbines, fracking), transportation (utility and service lines, cell towers), human disturbance (recreational activities), pollution (ag and forestry effluents), invasive species, and climate change.

Similar Species in Alaska: Sharp-shinned Hawk and American Kestrel

Sources of Information:

Audubon, Guide to Birds of North American. Downloaded on May 16, 2019 at: https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/merlin

Baicich, Paul J. and Harrison, Colin J.O. 1997. Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds, 2nd Edition. Princeton Field Guides

BirdLife International 2016. Falco columbarius. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22696453A93562971. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22696453A93562971.en. Downloaded on 16 May 2019.

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. All About Birds. 2017. Downloaded on 16 May 2019 at: https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Merlin/id

Dunne, Pete. 2006. Pete Dunne’s Essential Field Guide Companion: Comprehensive Resource for Identifying North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin Company.

National Audubon Society. Audubon: Guide to North America Birds. Downloaded on

Todd, Frank S. 1994. 10,001 Titillating Tidbits of Avian Trivia. Ibis Publishing Company.

Warnock, N. 2017. The Alaska WatchList 2017. Audubon Alaska, Anchorage, AK 99501.